Ten Highlights of the Travelquest Silk Road Tour

China 2008

by Pauline E. Abbott

1. The Eclipse (of course!)

I know some diehard astronomers complained that this was not a `perfect’ eclipse, because a few clouds provided a little frustration and suspense to accentuate the emotional effect of its glory. Haven’t they heard of foreplay?

First contact was called at 18:09pm. An echoing cheer went around the site. There was great excitement as cameras started recording, but also growing anxiety as clouds continued to drift across the vital area. We donned our eclipse sunglasses to take looks at the small bite out of the sun, growing ever larger. The air grew cooler, and the scene became darker, with that darkness peculiar to an eclipse. There is less light, but objects, and people, seem to glow.

The sky was mostly clear, but patches of cloud drifted over the sun from time to time. We prayed that totality would occur in one of the gaps! At about 18:50 things looked bad – quite thick clouds leaving parts of the site in shadow, parts, like the hill behind us, still in sunshine. Suddenly someone’s nerve must have cracked, and, like a panicking herd, others followed - a flight of astronomers picked up their carefully aligned equipment and ran, wildly, towards the sunny slope. We could see, though, that the cloud was moving in the right direction, and we stood our ground. Seconds later our decision was confirmed as many raced back!

The shadow of the moon was now surging towards us, coming quite clearly over the sand. Almost magically, the last wisp of cloud was gone, the crescent flashed with the first Diamond Ring, and we had totality – clear, and beautiful, and awesome.

There was a communal cheer, and sigh, from the crowd, all the more heartfelt because of the sudden reprieve from frustration. I felt a gasp of relief in my throat, and thanked the universe for such beauty. The sun’s corona streamed out around the deep black hole in the sky. The scene was dark now, with a 360 degree sunset all around us – all the more beautiful because of the clouds!

Totality passes so quickly. There was time to take one or two pictures of the scene, not expecting them to convey the miraculous beauty, but to remind us of the experience. One minute and fifty four seconds after the first, the second Diamond Ring glowed brightly and briefly and was gone.

The scene gradually wound down as light returned. Astronomers asked each other anxiously `Was it good for you?’

2. Fellow Travellers

Something about Travelquest’s special-interest tours attracts weirdos, oddballs, obsessives, and other intelligent and interesting people. On no such tour have I failed to enjoy fascinating conversations, wicked humour, mental stimulation on topics I’ve never considered before, all shared with tremendous good will and kindness. I hesitate to single out examples, because much of this interchange comes about simply by mingling a variety of people willing to participate with others in an unfamiliar situation. Who started the star rating system for the toilets we encountered, from the 5-star variety in some hotels, through the 2 or 3 stars encountered `in the field’ (sometimes literally!) to the minus several stars of certain holes that were not only flush-free, paper-free, lock-free, but also door-free? Who did not carry some map, GPS system, guide book, train schedule, who was not eager to share it with everyone? Who suffered the weight and security hassles of telescopes, tripods, video cameras, timing devices, who did not urge other observers to share a look on-site? Who did not pester our guides with searching questions to examine the `real’ China behind the official propaganda?

I do have to single out Tom Stockebrand. I found Tom’s interest in absolutely everything, his need to know how things worked and what things meant, very endearing. My first encounter with Tom was at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda, when he described with glee his discovery that in Chinese astrology he and his wife are `goats’. Though not all of his conversation was intended for me, in a confined tour space I find it impossible not to eavesdrop (sorry, Tom!) On one long drive his attention is caught by the posts and wires alongside the road, and he is intent on working out their purpose, what they carry and how and why they carry it, even down to the tension in the wires and the way they are attached to the posts. Listening to his quest enhances my journey, too.

Finally, Tom bequeathed a question he continues to ask himself - `Why do you travel?’ He had thought about it for some time, and decided the answer is `Because I’m curious.’ I am still enjoying trying to answer this question for myself.

3. Interactions with Local People

Limited by a short time in an unfamiliar country, such interactions happen most often while shopping. And, to experience a personal interaction you have to stray away from the tour experience a little. Shopping with the group means being led as lambs to the slaughter through, for instance, a local jade factory. This separates `us’ from `them’. In Xian, for instance, first we had to be educated on jade by Alex, who held up `real jade’ so we could see the light through it, and then held up `fake jade’ – in this case, obviously cheap green plastic – so we could see the difference. He pointed out the various areas of the store – the `masterpiece’ section, the `real jade’ section, and the `souvenir’ section, and let us loose. You couldn’t eye any piece of sculpture or jewelry without some eager young assistant coming to tell you how magnificent it was, accompanied by a clone who would offer a fifty per cent discount because of their `sale’, plus another ten per cent because you were obviously such a nice person. Walking away, you would often be asked `What price would you pay for it?’ Speaking for myself, I am really turned off by this procedure. It makes me feel the seller is testing to see how much of an idiot I am.

In Hami, on the other hand, we discovered a narrow street full of little stores and restaurants, where many Hami citizens were out enjoying the night air. David and Joan were the most confident, happily entering shops, pointing, writing, figuring out prices, and especially since she is tall with long blonde hair this did soon attract an interested crowd. They inspired the rest of us, and soon we were pointing and bargaining in our turn. The local people were curious, but in a very friendly way. Babies were held up to us – I’m not sure if they were showing us the baby, or showing us to the baby – and our waves and smiles and `hellos’ attracted replies in kind. In each shop, people gathered to witness our strange ways, pointing and giggling, but seemingly with us rather than at us. There were shops of all kinds. David and Joan bought themselves little folding stools, and a sleeping bag for the equivalent of about three dollars, figuring they could use them at the site tomorrow then give them away. We all bargained for peelable fruit – Jim bought a huge delicious mango. We three women bought yards of white cotton to spread on the ground to see shadow bands, or to use for extra shade. The lady in the store was proud of herself for writing down numbers, and understanding what we wanted, and was cheered by our group of followers at her successful transaction. Then, around the corner, we came upon a bakery! A young family member helped out here with signs and numbers, while an older one counted out our provisions. I bought a dozen cookies for about a dollar. Everyone was very friendly, very curious, and completely non-threatening.

My other personal shopping experience I undertook completely alone. I always try to find a Cinderella book in the language of any new country I visit, and I had noticed a bookstore about a block from our hotel in Urumqi. The bookstore was huge, and daunting, in that the headings over the different shelves were incomprehensible to me. I made my way round, peering at pictures on covers that indicated business, history, fashion etc. etc. Two or three clerks were eager to help me, but spoke no English. I tried to mime the Cinderella story in a questioning manner. They called in a cashier, who spoke a word or two of English and a few signs, and she indicated `No’ and `Third Floor’.

Up I went, looking for fairy tales in general and Cinderella in particular. In the children’s section I found a recognizable Disney Cinderella translation, so I knew it was OK, but these generic versions disappoint me a little. I really like native illustrators, and preferably the ethnic variety of the story (though, admittedly, I couldn’t discriminate that well in Chinese!) Anyway, moving along the shelf, I found a homegrown version that looked like Cinderella and Other Stories, as the pictures evolved into red hoods, beanstalks, pigs etc in later pages.

I returned to my English-understanding (?) cashier. She nodded at my choices, but at the second said firmly `Cinderella yes’ to the front cover, `Cinderella no’ waving her hand over the other pages. Since the total came to between nine and ten dollars, to her delight I bought both!. With a spring in my step I made my way back to the hotel, my quest completed, and having thoroughly enjoyed the fun of abandoning my acting inhibitions and sharing laughter with friendly sales clerks.

4. The Train

Travelquest had reserved the whole of the famed China Oriental Express exclusively for our party. It has been used in the past to accommodate senior leaders of the Chinese government or distinguished foreign guests. The cars reflect classic 1930s – 1940s style, with rich wooden décor, comfortable double sleeping compartments with table, seats, and brass lamps, curtains, air conditioning, ornate plumbing between each two compartments, carpeted corridors, a piano bar, two dining cars. At each end of each car a uniformed attendant sits, to bow and smile as you pass, or to provide coffee or tea at your whim. We arranged ourselves enthusiastically around our temporary home in car 8, exclaiming at the fittings, the elegance, the luggage space, and, a lovely surprise, the two of cups of hot tea delivered to our table. We explored along the corridor, greeting others settling into their rooms, and being visited in our turn.

On our one night aboard, I reached out and pulled back the curtain, to find we were traveling through a dark desert landscape, with only a slight glow from the light of the train. Then I looked up – and was enchanted to see how many stars I could see in the deep black sky. They shone so brightly by contrast.

Some transitions between the cocoon of the train, and the rest of the world, came suddenly, but not for want of trying to alert us gently. At 6:00 am on our first morning tranquil meditative Chinese music began to play softly over the train’s speakers, rising gently in volume over a few minutes. What a delightful wake-up call! Less gently, for our first disembarkation, a sweet little Chinese voice came over with a succinct message in obviously limited English - `Get out!’

Along the route the changing scenery had to be observed and, if possible, photographed. I had a map, and took pleasure in noting the names of stations through which we passed, to chart our progress. Ethnic meals were regularly to be shared, their contents analyzed and savoured with fellow-diners. Coffee and conversation were available in the bar, once with piano accompaniment. Interesting lectures were arranged – I learned more about eclipses, Chinese history, the religions of China, the geology of the areas through which we passed, Chinese politics … There was always something to do – and, the choice to do nothing but relax among new friends.>

5. The Terracotta Warriors

Ying Zheng was born in 259BC, the son of the king, and he became king himself at the age of 13 after the death of his father. In 221BC he achieved his goal of conquering the six other states around Qin, and declared himself the first emperor of a united China. His further achievements included a centralized government administered by himself, standardization of weights and measures, simplification of script, the building of a road network, regular reports from all parts of his domain, restoration of the Great Wall, and the elimination of viewpoints opposed to his own by burning of writings and the murder of their writers. One of his major projects was to construct an enormous mausoleum for himself, with pits of terracotta soldiers to protect him. He died while away from his tomb on a tour of his kingdom. Scheming politicians diverted his letter naming his older and wiser son as his successor, crowned a younger and more manageable heir, and under his incapable rule the Qin dynasty came to an inglorious end only fifteen years after it had begun.

700,000 workmen and craftsmen had been involved in the mausoleum’s construction, and along with the emperor’s childless concubines many of these were buried alive with him, so the site of his resting place should remain secret.

According to the party line and the official guide book, it remained a secret until March 29th 1974, when a local farmer digging a well fell into a hole full of pottery and reported it immediately to the authorities. The area was sealed off and properly investigated, and the farmer was given a government pension. The first pits were opened and painstakingly excavated; others have been left intact and unexplored until the technology to preserve them can be invented and afforded. The dramatic story of the discovery can be authenticated by the now 79 year-old farmer who reputedly sits at the museum and signs guide books. (However, photographing him is forbidden, and when we get there he has `gone for a nap’ leaving many signed books behind him, so we suspiciously wonder how many `farmers’ are employed in this dramatization.) A less official guide book, obviously translated from Chinese into picturesque English, confesses that `terracotta bugbears’ were found frequently by local diggers, who considered them a real nuisance because they `raised the devils, and made the new grave fallen down suddenly as well as the water in new well exhausted.’ Also the `bugbear sometimes appeared on the well wall abruptly and bulged mouth and goggled at the farmers.’

Whatever the truth of the discovery, at this point the terracotta army is an impressive and awe-inspiring sight. The figures are life-size and lifelike, though exposure to the air has faded their former natural colours to a uniform sandy monochrome. The sheer size of the display is overwhelming – the pits stretch as far as the eye can see under a mighty protective roof. As you look, you make out the individual characteristics of the ancient faces. No two are alike. Ironically, the Emperor has ensured a kind of immortality for the craftsmen he buried alive. Each was told to carve his name on the figure as he finished it. If there was any imperfection in the work, the emperor would know whom to blame! Now, though, the names are recorded and revered. We feel pleased at this slight karmic redress – how improbable, looked at rationally, that one man should have so much power over his subjects, and that his skilled craftsmen, not to mention his concubines, should have been considered completely expendable.

6. Asparas at the Mogao Caves

Of course I include myself in my earlier characterization of Travelquest travelers as `weirdos, oddballs and obsessives’. I confess one of my own most lasting obsessions – an interest in the angelic archetype. The way in which various religions, or cultures, or individuals, personify or represent forces for good in the world is a field of rich psychological and anthropological interest.

The Mogao Caves are about 15 miles south of Dunhuang. The caves were dug out of a cliff face by Buddhist monks, who lived there and decorated them over a period of about 700 years, from the 4th to the 11th century. They also became the repository for Buddhist manuscripts, sutras, texts and silk paintings over the same period. Some time in the 14th century they were sealed up. In 1900 a monk called Wang Yuan Lu came upon the caves by accident, and decided to make it his life’s work to restore them. In 1907 Wang and his treasures were discovered by the British explorer Aurel Stein, who, for a derisively small donation, took away many of the manuscript treasures. Later a French explorer did the same thing. Many of the caves’ most precious treasures are in the British Museum and the Louvre today..

Over 500 caves survive, but only about 30 are open to the public. To visit even these, you must be accompanied by a guide, and, to get the full benefit, you should take your own flashlight. A guide will flash her torch at what she describes, but apart from that you are on your own in only the light from each cave’s entrance. We were told only 25 guests could enter at one time, so we would all have sufficient air to breathe. Unfortunately, once inside the groups of 25 got into `shifts’ with Chinese-speaking groups (this is a popular Chinese tourist attraction), so in each cave the echoes and voices of more than one language rendered my visit more mystic than informative.

The memories I brought away are these. Our first cave, no. 130, contained a huge seated Buddha whose enigmatic smile and finger-gestures were way, way up above us in the dark heights of a cave several stories high. We walked, like tiny Lilliputians, around the crevasses of his toes and the curve of his knees. We admired in cave 135 an example of a kind of medieval `strip-cartoon’ of an ancient Chinese myth, successive sections each illustrating part of the story in which Buddha gave his own life to feed a starving tigress.

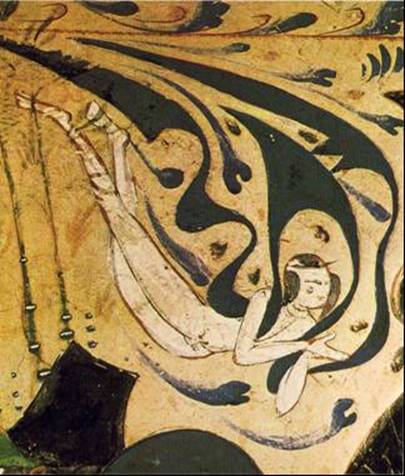

And, most significant for me, in several caves our guide pointed out illustrations of something I had known, but had forgotten – that Buddhism has its own way of portraying angelic figures. Known as apsaras, or sometimes referred to as devi, these figures’ ability to fly is represented not by symbolic wings, but by whirling `scarves’ and garlands billowing out in intricate patterns. Once these are pointed out, I see them everywhere – and continue to see them not only in these caves, but in the décor of stores, railway stations, etc.

7. My First Camel Ride

A surprise, as we passed under the entrance archway of the scenic tourist oasis, was the sight of such a horde of camels, and the pungent aroma of camel that wafted towards us. Over a hundred camels knelt patiently in the sand, their minders bustling up and down between them collecting tickets, and their walkers nudging them into their well-trodden route. As a line of about five camels formed, a walker would lead the line out across the desert sand. I found myself prodded by one of the minders towards the best-looking camel on the mountain, at the head of a line.

The Bactrian camels each had a substantial and richly carpeted saddle between their humps, with a firmly fixed safety bar. The reasons for these became apparent as the camel rose from its recumbent position. At a word from the walker the camel unfolds like an expanding trellis as various joints in its legs unbend and click into an upright position. A sharp jolt forward, a sharp jolt back, and I was aloft, at a point of no return.

At the far end of the route my walker made arcane gestures at me, which the traveler behind me correctly interpreted as `Give him your camera.’ Trustingly I did so, and he took a picture of me and my steed. Then came the dismounting. `Hold on!’ A lurch forward, a lurch back, and we were neatly folded, with the ground within my reach. I had completed my first camel ride!

All this happened in the foothills of the Minsha Mountain, an area famous for the qualities of its sand. The movement of the sand is said to make a thundering sound. My favorite guide book offers a few possible explanations for this –

1) the sound comes from sliding sands whose interspaces change differently so that the air would go in and out over and again

2) the resonance produces while the seismic wave of dried sand being transmitted to the layer of sand soil under the sand dune

3) the exterior of sandy mountain is very dry and rich in quartz, the sands rub each other to make a sound while wind blowing and people going round on them in the sun

4) the quartz is sensitive to the pressure, the static electricity occurs while being continuously extruded and conversely it telescopically convulses.

Pick whichever scientific explanation you prefer!

8. Chinese/English Translation and Communication

In China I am illiterate. It is a salutary experience for me, having spent my working life teaching reading skills to students with learning disabilities, to suffer such a disability for myself. Printed notices, posters, warning signs, books in bookstores, are here nothing to me but a meaningless pattern of strokes and curves. It is uncomfortable, yet I must count it as a highlight, for it stretches my brain into unaccustomed ways of thinking, and the devising of new coping skills.

The passage from the guide book I quoted in the item above is an excellent example of the delights of reading information that has been translated from Chinese into English. It is amusing and entertaining. I assume translations from English to Chinese are equally droll. I know from my facility with French, German, Spanish that even in these languages with many common cognates and other hidden clues from shared associations, it is not enough to consult a dictionary and expect to find correct vocabulary equivalents. Do the Chinese communicate concepts through their complex symbols that we can never understand? Are the Chinese really inscrutable?

The gap between their educated and peasant classes has been lessened by the reduction of approximately 70,000 glyphs to a mere 3,000 said to be necessary for routine communications, and the introduction of a `simplified script’, but is translation possible only at that simplified level? Can only simple concepts be exchanged between those trained in either culture? I become increasingly aware of the difficulty of subtle translation between two such rich languages.

Spending time in an alien culture lends some objectivity on one’s own. Our simplification of code to 26 letters of the alphabet has certainly enabled greater levels of literacy. Has this simplification increased, or decreased, our erudition? Has our simplification of the code made us more efficient, or less subtle, or not?

Do the Chinese know what they are missing in the pleasure of doing crosswords? And is the English-speaking world returning via its increasing use of symbols, logos and emoticons to the glyphs from which our alphabet descended? Such are the possibly pointless but enjoyable musings invoked by my exposure to the Chinese written language, and they are a major highlight of the inner explorations evoked by this stimulating environment.

9. Heavenly Valley and the Cable Car

Heavenly Lake, or Tian Chi, is about 60 miles east of Urumqi, and about 6,500 feet above sea level. Enclosed by snow-capped peaks, luxuriant meadows and dense pine forests, it is a complete contrast to the arid desert areas around. The local ethnic minority here are Kazakhs, who live on sheep and tourists.

A bus drive brought us to scenery reminiscent of Switzerland, with sunflowers and poplars on the lower slopes, soon rising to pines on jagged hillsides that looked more Chinese.

We walked up, then down, to the edge of the lake. Spectacular pagoda-like boats were moored there. Ours was smaller, but we got good seats at the back in the open air. As we pulled out onto the lake, magnificent scenery surrounded us – spectacular snowy mountains in the far distance, green hills in the foreground, and a view of many walking paths and interesting weeds around the edge of the lake. Artistic builders had popped the odd pagoda on ledges, accentuating the crags.

In our free time after the boat ride I took one of the walking paths. There were many kinds of wildflowers, and a bright yellow butterfly posed for my pleasure. I found two lovely signs, obviously literal translations from the Chinese –

`The green grass is afraid of your tramping,’

and

`Have mercy on the green grass.’

We had the choice of returning by shuttle or by cable car. Who wouldn’t take the cable car? We lined up, and two by two were seized, pushed into seats, and cast off. For me this was another highlight of our trip. We were up in the clear mountain air, looking down on spectacular scenery. Happy Chinese music tinkled gently through our loudspeakers. Every now and then we met fellow travelers swinging their way up the hill on the adjacent cable. The natives were overwhelmingly friendly – many smiled, waved, giggled. and called `Hello!’ to which we responded with our own calls and smiles. These brief uncomplicated exchanges seemed to surround us with a great feeling of international goodwill.

10. Culture Shows

The Beijing 2008 Olympic Games have made us all more aware of the Chinese government’s practice of training young children, from a very early age, if they show aptitude for acrobatics, athletics or gymnastics. Whatever the ethical arguments for and against this practice, the results are spectacular. Slim young figures perform seemingly impossible feats of agility, balance, precision and skill.

Our first Culture Show in Xian offered many examples of these. A little like opera, or ballet, the accompanying plot line was merely an excuse to string together virtuoso displays. We didn’t really need to understand it, which was just as well. There was an Emperor, there was a concubine, there were many entertainers who came to court. There was some problem which needed sorting out by dancing warriors and, as far as I can tell, all ended happily. The costumes and settings were splendidly glorious, in rich colours. The dancers were all young, and lovely, and unbelievably acrobatic. They had fixed smiles if they were good guys, and fixed glares if they were bad guys. Among the entertainers who came to court were a team of young girls who looked about ten years old, and who performed the most amazing acrobatic feats while simultaneously balancing and throwing diabolos. Their skill was flawless.

A second Culture Show in Dunhuang was another feast for the eyes, even if the story was a little incoherent. It was based on the story of Deer Girl, the mother of China, depicted in one of the Mogao Caves. Two amazing little girls played the main roles. There was a supporting cast of emperors, warriors, shepherds, demons, and other dancers and acrobats. English subtitles tried to keep us up with the story, but were confusing in themselves. The syllabification was arbitrary – a line of type would end anywhere in a word, but it didn’t matter. We gave it enthusiastic applause.

Our final Culture Show in Turpan was remarkable for the friendliness and enthusiasm of its performers, local Uighurs. Mahmoud, our guide, had said they were all very excited by our visit, and would be even more so if we participated. They did seem to be happy amateurs, rather than the sophisticated Chinese performances we had seen earlier, and were none the worse for that. Their dances were more folk dances than demonstrations, and they did, indeed, come amongst us and persuade various travelers to join in the dancing on stage. I’m pleased to say the Blue Bus representatives acquitted themselves very well.

At the end a local dancer found himself center stage and at a loss for words. `Stop!’ he shouted. There was a burst of laughter, with him, not at him, as a swift translation explained that he meant to say something like `Our performance is over. Thank you for coming.’

And, my summary of highlights is over. Thank you for reading. `Stop!’