Painting the Big Island - Hawaii

February 2006

In February 2006 a group of twenty three artists joined with a master to do plein air (painting from life) watercolor for nine days on the Big Island of Hawaii. Having already enjoyed painting on location in many countries around the world, why have I not done this before? Painting all day, every day is a luxury I have never given myself, and I was not sure how I would handle it. Maybe wishing for more time to paint was just an excuse for not painting more. What if I got here and got tired of painting all the time? What if I got here and joined with artists so good that I quickly found myself out of my league? What if the great secret that I am not really a great artist finally got out and removed an age-old morale booster from my tool kit. This trip would answer such questions. Am I really ready for the answers?

After deciding to join the workshop, which had been organized by California artist Timothy Clark, Pauline and I had another decision to make. Would she come with me? I anticipated a trip designed for artists with everything an artist would want for the duration, and nothing more. Whether she would fit into that scenario was the question. After some discussion she made a very wise decision to visit her relatives in England instead, taking advantage of cheap winter airfares. A number of people remarked that choosing England over Hawaii in February was something short of insanity. Actually, they would be dead wrong in this case.

After a few hours sleep, still dark outside, I hit the freeway for the LA airport to meet the group at 7:30 AM. The fast moving traffic tricked me into thinking I would be there an hour too early, since on the best days I can make LAX in 30 minutes. My concern flip-flopped when the freeway became a parking lot at Long Beach, and I began to think I would be late. Creeping along in stop and start traffic miraculously placed me in the airport almost exactly on time. Unfortunately, the others who left later were still sitting on the freeway. By the time the entire group assembled, we barely made the flight, with doors closing just behind the last of us. After arriving in Kona, we formed a caravan in an hour’s bumper-to-bumper traffic on the only highway (mostly a two lane highway) that circles the island to the Manago Hotel in Captain Cook, Hawaii.

The Manago Hotel, a family owned historical landmark and one of the oldest hotels, sits on a hillside about 1200 feet above sea level, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. My room was equipped with a bed, a radio and a fan and, best of all, a second floor balcony overlooking Kealakekua Bay to the west.

Hawaiian names are difficult to say, and even more difficult to remember. If you don’t learn to say them, you won’t remember them. The 12 letters in the Hawaiian alphabet must repeated over and over to produce enough words to make up a language. After saying words a few times, however, the rhythm is beautiful and fun and begins to make sense.

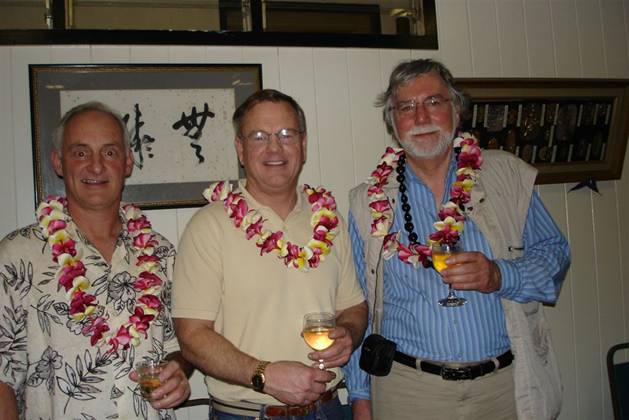

The lack of telephone, TV, internet, pool, Jacuzzi, etc, took a bit of getting used to; however, in the end, the lack of distractions served an important purpose for this group. We had nothing else to do but paint. The lack of sidewalks, streetlights, and flat surfaces made it difficult to exercise or even take a decent walk at night since almost any direction, except along the busy highway is steeply up or down. A Choice Mart grocery store within a short walk from the hotel made it possible to acquire the necessary staples, such as pineapple wine, beer, and Jack Daniels, and a U.S.A Today. By the time I had finished the USA Today and few glasses of wine, the reception started in the formal Japanese dining room, where the group began its first attempt to get acquainted. I made my first faux pax by forgetting to remove my shoes when entering. Nevertheless, I still received a lei, a nice glass of wine, and my first bit of the famous “aloha” of Hawaii.

Workshop reception at the Manago Hotel-Zeke, Jeff, and the WWT

Dinner was over by 7:30 and there was little else to do. I walked in the only lighted direction down a side street towards the ocean, having no idea that the ocean was three miles away and 1100 feet down. Descending at a fast clip, I realized that the walk back up would have to be taken into account. Deciding that the ocean was not a walking option, I turned back up the hill, not a minute too soon. My huffing and puffing had awakened every dog in the neighborhood and they all began barking.

An early night to sleep suited me fine since I had gotten little sleep the day before. Going to sleep was easy enough; staying asleep was more difficult. The jungle behind my room was inhabited by every noise making bird known to man, including a half dozen roosters who tried to out do each other starting sharply at four thirty in the morning.

We met each morning at 7 AM, ate about twice the breakfast we normally eat, and heard instructions for the day’s painting site. The fresh papaya, grown in the grove behind the hotel, had everyone addicted by the end of the week. You have not eaten papaya if you have not had it in Hawaii. Attempting to replicate the experience back at home left me with a box of papayas from Costco, still not ripe enough to eat a week later.

We spent our first day painting at Ho’ Okena Beach, about fifteen minutes south of the hotel. Tom Jove and I, sharing a car, were first to arrive at the beach, which lay at the end of a narrow, winding, two-mile road. It was a local’s place, comprising a packed campground on one side, a few run down houses, a lot of local bathers and not much else. My first impression was “There is nothing worth painting here. Could this be the wrong beach?”

After walking up and down the beach and still not seeing anything very interesting, besides the ocean and a few palm trees, I saw Tim setting up for a lecture demonstration near a few picnic tables. I joined the group and listened. “This place is even better than I remembered it,” he exclaimed, enthusiastically, as he set up his easel facing the campground, looking at a group of tents, campers, trashcans, signs, and concrete barriers. It was difficult for me to get excited about painting something I would never think about photographing. We had come 2000 miles to see a painting of a group of generic campers, possibly the least photogenic scene in all of America; the only thing that was vaguely interesting was a palm tree, badly in need of considerable manicuring, sitting amongst the tents.

Ho’Okena Beach Scene selected by Tim Clark for a painting demonstration.

He began sketching the campground scene before him, stopping now and then to describe composition methods he was using, designing and planning the painting, a technique called “wedging”, where a scene is made more interesting by wedging additional features together. To illustrate his point further, he slipped a fresh piece of paper onto the easel and drew a part of the scene again, this time with people standing in a group amongst the trees. Then he added a truck, and going still further, drew the front end of a large pontoon plane entering between the trees, hesitating occasionally to snap at someone in the group for either disbelieving him, making too much noise, or standing in the wrong place. He laughed at the pontoon plane, which looked surprisingly artistic sitting amongst the trees. He was obviously proud of his airplane and he commented, “I never drew a pontoon plane before.”

Ready to begin painting, he returned to his first drawing, and rolled out a canvas brush holder dumping a pile of well-worn brushes in a heap. He began an almost continuous monologue as he prepared a sheet of paper and paint. “I checked to see if there was an award for being gentle with brushes. There wasn’t. I have known artists whose only claim to fame is still using the same brush for forty years.” He pulled out a watercolor pallet that could be in the Guinness book as the messiest possible pallet. As he dabbed two brushes alternately into water and paint, paint appeared to be flying everywhere. Someone reached for a brush that appeared to be slipping onto the sand. “Don’t touch my stuff!” He snapped. I had learned long ago that touching Tim’s “stuff” was about the worse thing an on looker can do.

It was a clear day. Tim began covering the paper almost entirely with an orange wash. He paused and looked around at the group. “You think I can’t have an orange sky?” he challenged. Continuing his routine, he added smears of various colors, stopping from time to time to point out how well the colors blended and the beautiful result, partially planned, partially unpredictable. Beginning a comment on the relationship of colors, someone attempted to finish his sentence with “the complementary colors will strengthen each other.” “Don’t help me!” he snapped. I began to wonder if he would leave out the dead, yellowing and drab gray leaves hanging from the palm tree, some having already fallen in a dead heap at the base of the tree. A stream of paint ran across the painting. “Are you worried about that?” he asked. “Then don’t. It is not a problem.”

After about fifteen minutes the paper was covered with a total mess of colors that resembled very little of what I could see in the scene. “I like to keep the painting as messy as possible as long as I can.” He laughed. “It keeps the gawkers away.” And so began a story of some lookyloo that had once bothered him, and how to deal with them, waiting strategically for the wet surface to reach the right state for the next paint. Little by little painting negative and positive spaces, he removed and added structure to the surface and the painting began evolving into something that seemed to make sense. “Just don’t call it ‘negative’ painting,” he warned. “That is a mislabel.”

“I know what some of you are thinking,” he posed to us. “How the hell is he going to get out of this mess he is in? Tell me, however. How many of you could take it from here and finish?” Clearly most of us could see where he was headed and answered positively. But I have to admit, on more that one of the dozen or so similar demonstrations I watched during the next few days, I did often think to myself, “How the hell is he going to get himself out of this mess. Surely, he has royally screwed the pooch this time!” But he always recovered and pulled a beautiful work of art out of the mess of colors. At this point he shouted at someone who had been taking pictures of each stage. “Don’t do that! It bothers the hell out of me.”

An hour later after a dozen jokes, pauses to point out a method, a few more insults, and stories about former teachers and friends, a beautiful painting evolved based on a scene that I would never have looked at twice before that day. The dead leaves had become a striking blend of red, yellow, and purple, It would never have occurred to me to paint these anything other than gray…or else to leave them out entirely. They had become the most beautiful part of the painting. It did not seem to matter that the colors he had chosen for some parts of the painting bore little resemblance to the actual scene. The colors worked.

Stepping back a bit, I should introduce Tim Clark, who may be one of the best, if not the best, art teacher in America. His passion, devotion, skill, and sheer boldness in art combined with his intelligence, excellent memory, and self-confidence make him a true powerhouse in the art world. In addition to these, with an ego just as large, he always commands the center of attention in a gathering. The art world would benefit if fewer of its heroes were drunkards, dope addicts, and suicidal maniacs, and more with the kind of focused unlimited energy exhibited by this one.

Few people have the rare talent of getting away with insulting people, while some of us get busted for the slightest slip of the tongue. Tim uses insults to make a point, to get attention, and sometimes, seemingly out of habit or for practice, or for reasons completely beyond me. He usually gets away with it and it seems to work for him. On a scale of one to ten I would give Tim a 9 in the ability to use insults constructively. When his insult fails he usually realizes it and quickly retracts or at least apologizes for a comment. An older gentleman, who had accompanied his artist wife to a lecture, complimented him for doing such a good job. Without hesitation, Tim asked, “What qualifies YOU to say how good the job was.” Later I heard him apologize for such an insensitive response to a well-intended comment. By the time our trip was over I felt somewhat honored to have been insulted at least as much as the others and on one occasion to have received the ultimate “F**k you!” in response to one of my own playful insults.

Tim has an amazing repertoire of interesting anecdotes about teachers and fellow artists, as well as an unlimited number of jokes and character imitations that he amazingly fits into demonstrations and lectures to establish a point. He skillfully employs these as tools for keeping the audience attention as well as to buy time when needed for paint to dry. A story can go on and on and then magically come back with a punch line that makes the point that he is teaching. His classes are continuous entertainment combined with instruction. All of these combined with his art and unique personality are well known in the art world,

After the ninety-minute lecture demonstration, we all spread out, some choosing to recreate what Tim had just done and others wandering off to look for something more exciting. At this point I was not convinced that I could turn the scene into something beautiful the way Tim had done. My first criterion for a scene was that it must face a spot in the shade where I could sit out of the hot near-equatorial sun. I was not ready for second-degree sunburn. The only thing even mildly interesting to me was a row of outrigger canoes stacked upside down in front of a palm tree. Soon I was immersed in drawing the details of the scene, and the more I worked, and the more details I began to see, the more beautiful the scene appeared to me. Then I discovered that was exactly what Tim had insisted that we not do.

I have no problem drawing anything before me, and most scenes become beautiful or at least interesting to me when I draw them. Nevertheless, I felt pretty inadequate, having just seen Tim’s skills with watercolor, what to do with the paint, how to choose colors, and how to wait for the paper to be just the right wetness. Up to this point, my job as an artist was to draw and paint exactly what was in front of me. I began by throwing in some clouds that didn’t really exist, just for fun. By lunch I had a pretty boring painting that pleased me just slightly more than the scene I based it on. It was neither beautiful nor interesting. The overcast day had presented almost no shadows for me to place. The clouds were not my best and even the canoe was not very interesting from the vantage point I had chosen.

After we had all feasted on sandwiches and fruit, Tim collected all of the paintings and began, one by one, to give a detailed critique of each. A few of the paintings were respectable, but most looked, as mine did, and to my relief, somewhat amateurish. The people who had painted Tim’s scene had failed to recreate Tim’s magic. I had managed to wedge in a few people amongst the trees to apply one of the techniques he had instructed. Surprisingly, he complimented me for that and mostly criticized my choice of “Pee Wee Herman” green for the trees. At that point I realized that I had not really learned what happens when green and red are mixed in various amounts. In several years, I had struggled to produce a good gray and black, and such a simple maneuver had evaded me through a lot of watercolor instruction. During the next few days, with this great new door opened to me, I used so much green and red that I almost ran out, and Tim was still not satisfied with my ability to mix and distinguish the different hues and intensities.

After lunch a few people went swimming. Others, including myself, decided to continue painting. I fooled around with my first painting until I accepted that it was a lost cause and started a second painting, similar to that which Tim had done earlier. It was worse than my first, clearly showing my disinterest in the subject. When others began to pack up, I continued on for a while until I realized that my painting was never going to look like Tim’s. Somewhat discouraged, I packed up my equipment and headed back to the Manago Hotel.

We stopped for shopping at the ChoiceMart near the hotel, where we purchased a few more snacks and items for the next day before returning to the hotel. I was a little depressed and was delighted when I heard Zeke shout from the deck just above, “Jim, come on up and help us drink this Jack Daniels.” It was then that I discovered how good macadamias taste with whiskey to wash them down.

Dinner was at a nearby seafood restaurant, the Kai Café, where I feasted on some of the best seared ahi I had ever had. Our group comprised five men and eighteen women. By now I knew the names of three or four people. I sat between Kathy and Carol. I recognized a few women I had seen in art classes, but did not remember their names. In the course of conversations with Kathy during dinner, I discovered that she already knew the names of every person at the table. I asked her to help me with this, and, by the next morning at breakfast I could name every student. It was a great feeling for me, and I realized the similarity between this and becoming familiar with new places. Being familiar with our surroundings makes them less threatening, and I discovered this to be true with people as well. By the end of the adventure we were all like a big family, listening, helping, and encouraging each other.

During the next days we painted at three different beaches, a botanical garden, a coffee plantation, and down town Kona Kalua. The second day was somewhat a repeat of the first day, this time at Pu’uhonua o Honaunau, or Honaunau Beach. This beach was much more attractive to me, and possibly, the previous day’s experience had taught me to perceive a scene more like an artist. Again, Tim chose a scene that I did not see as paintable at first.

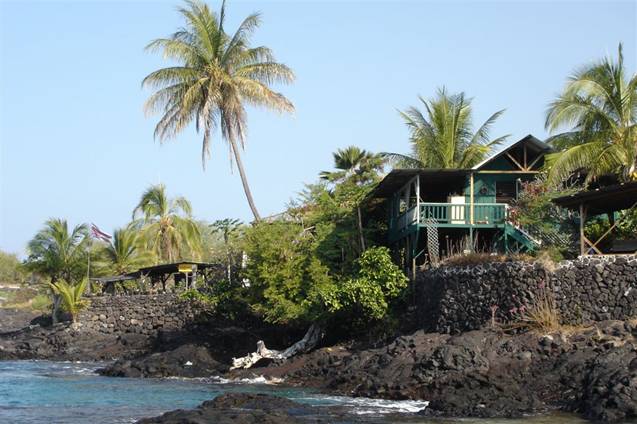

The focus of his painting was the pahoihoi lava bed that bordered the sea. In the background was a stretch of land with a few palm trees and a shack that I would have emphasized. He emphasized the lava bed, which to me was a dull gray to black. Once again, Tim’s mess evolved into a beautiful pattern of colors with a tide pool that I had failed even to see. I wondered if he could really see those colors in the pahoi hoi. Over and over he emphasized, “simplify, simplify, simplify. Start with a scene and remove some things.” It was not a sin to replace a group of trees with a swirling mass of green, or even to leave most of them out of the painting. “I can do things that even the corps of engineers cannot do,” he said, as he cut away a slab of pahoihoi in the painting to enhance the rhythm in the painting. Finally, the difference between a picture and a painting began to sink in. Still it took me a few more days to start trusting myself to slip this idea into my paintings. I liked the scenery here much better than that at Ho’ okena Beach. I picked a scene and included a house and started with the idea of simplification. Before long I found myself again drawing windowpanes, shingles, individual flowers, and details. At least the painting was pretty and interesting even if it was still more of a picture than a painting.

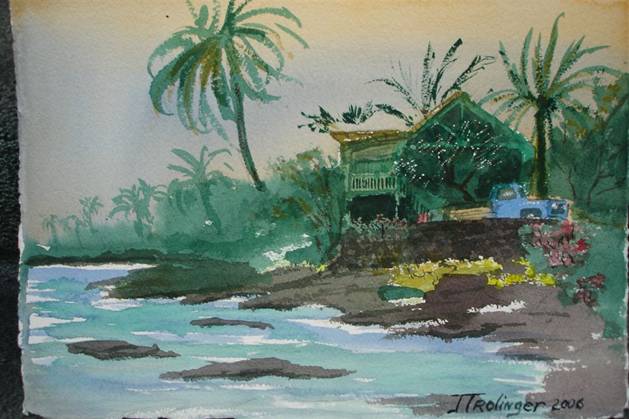

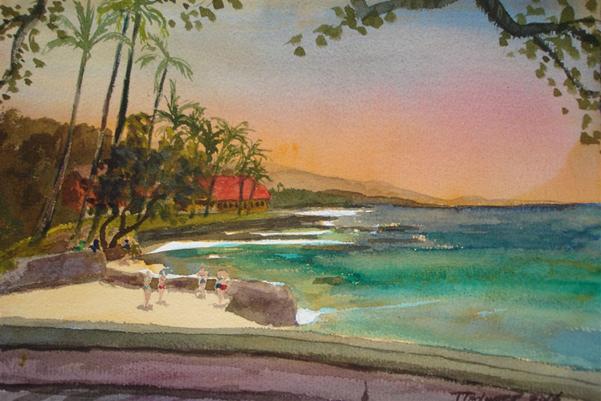

Painting scene at Honaunau Beach

My interpretation of the scene at Honaunau Beach

After lunch and getting dinged for doing so many details, Tim suggested I try painting left-handed. I went back and did a second smaller painting trying harder to use what I had learned so far. An onlooker from San Diego came back a second time and asked me if he could buy the painting. I told him that if he left his address, I would give it to him. I am not sure if he believed me or not. I think the second painting looked better, so I went home feeling better that day.

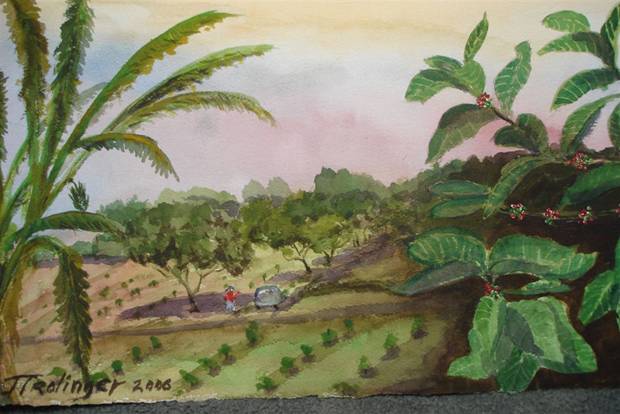

On the next day we painted at Greenwell Farms coffee plantation, and this time I was determined to paint less details. I sat on the side of a hill overlooking a field of coffee trees with a banana tree in the foreground on the left and a coffee tree immediately next to me on the right. After doing a decent job on the field and maybe even the banana tree, I became fascinated with the coffee tree, and before I had realized what I was doing I was drawing each bean on the tree. I had fallen in love with the first coffee tree I had ever seen. When Tim critiqued the painting, as always he made both positive and negative criticisms. “The berries are a bit too ‘cute’, but I can live with that,” he said.

Greenwell Coffee Plantation

My interpretation of the Coffee Plantation

Our Sunday evening dinner was a special treat of a wide variety of Japanese ethnic foods prepared by the younger Manago and served up in the special room. Before this night I thought that I had tried every edible Japanese thing; however, there were several that I failed to recognize. At the end of the meal the elder Mr. Manago entertained us with stories from early Hawaii. Some of his stories relating seeing the first car on the island and eventually secretly purchasing a car, without his wife’s knowledge, were funny. Eventually, when she discovered that she was half owner in one of these new fangled contraptions, she became so angry that she flushed the keys down the toilet. Other stories such as learning of the bombing of nearby Pearl Harbor and joining in the service were not so funny. He and his wife had started the hotel business and now passed it on to the son. During that period it was clear that Mr. Manago had made millions investing in Hawaiian real estate. He related stories about buying huge plots of land for a few hundred dollars an acre.

It seem as though each day the painting site was much more beautiful than that of the day before. Or more likely it was I who was changing my way of perceiving the site. The group had become more of a family by now, and we began to continue the days with drinks and even singing exercises. Alice, a local artist, also played ukulele and sang in a local group, so we enticed her into an impromptu show. A dozen of us gathered in her room and sang, while Katy, another Hawaiian, joined in and performed the local Hawaiian dances, and interpreted the hand movements for us. We all liked the hand expression for “happiness”, which was a gesture of spreading all five fingers upward over ones face accompanied by a big smile. By midnight we all began to feel like Hawaiians. The Jack Daniels made that a little easier.

Alice on Ukulele with Kati performing Hawaiian dances

After learning that I had once played ukulele in college, Alice described a local ukulele store, “Just Ukes”, that would be a good place to pick up a uke. A few days later she went with me to Just Ukes and helped me pick out a good one. Our choice was a Kalana, a well-known Hawaiian company; nevertheless, this uke, like every other uke in the entire store, was, somewhat to our surprise and disappointment, made in China.

The next day was President’s day and we chose to avoid beaches because of the crowds. Instead, Tim had obtained permission for us to paint in the nearby botanical garden. The day began with a demonstration of painting a banana tree to illustrate fundamentals he had previously described. “Don’t make all of the leaves equally spaced, even if they are. Some of you could turn a palm tree into a clock with twelve equally spaced leaves. Someday I am going to make a clock face out of a palm tree.” He didn’t like the exact spacing on the tree he was painting, so he adjusted it to make it more interesting and left out a few things that were confusing.

Tim’s banana tree. Notice how the tree falls right in the golden circle.

I strolled around the garden for half an hour looking for the perfect spot, finally choosing a location on the side of a hill. Zeke and Jeff had picked essentially the same spot, which led to Tim’s labeling us “The Hill Boys”, a name that stuck with us for the rest of the trip. Late in the morning he made the rounds and did a preliminary critique. “Your green needs more f##king red in it,” he whispered, in a chastening tone.

“If you can have an orange sky, why can’t I have a Hooker’s green tree,” I laughed.

The evening was an open night and we were to fend for ourselves. I took the opportunity to paint the view behind the hotel from my balcony. Strangely enough it had elements of just about everything we had learned so far and in a simple painting. By the time it became to dark to paint, I left my room with the idea to try the local chop suey house. I was not aware that it was raining until I reached the bottom of the stairs. Returning to the room for an umbrella, I ran into Zeke and Jeff, who had the same idea. No sooner than we arrived at the Chop Suey House, a small, locals, hole in the wall, two more of the troops joined in. The meal rivaled the best we had tasted all week. Maybe the beer, the companionship, and the motive had something to do with it.

The next day we visited the most beautiful beach yet, a private beach with no name; it was part of a modern phenomenon. In Hawaii, as in many such beautiful places, industry has a way of sneaking in and exploiting the beauty, sometimes to its detriment. It is the age-old story that beauty often destroys itself by drawing in so many people who want to live in beauty that it becomes ugly. At this beach a large company had almost sneaked one in under the radar. After a few thousand acres of beachfront property had been turned into a golf course and the building site for a hundred multimillion-dollar homes, the builders had managed to retain the farmland zoning, so each multi million-dollar home and the golf course were zoned as small farms with great tax advantages. An environmental group caught it and sued the state to halt construction. The entire project had been frozen in court by the lawsuit, and here sits the most unbelievable golf course on the beach with half finished homes that no one can use, frozen in time until lawyers finally come up with a scheme or pay off enough politicians to populate it.

Fortunately, among Tim’s many acquaintances is the son of one his most beloved students who is an officer of the development company, and he had arranged our group access to the beach. As an added bonus, Tim had convinced one of the law firm’s secretaries to model for us that day. After a demonstration we all then had our chance at drawing a beautiful Hawaiian model on a lava-covered beach.

In the middle of the demonstration, the model, who was gazing out to sea, pointed out a whale slowly moving across the foreground, surfacing occasionally to blow a large cloud of steam. Even though it was a significant distraction, we could hardly avoid time-sharing between watching the model, Tim’s painting, and the whale. Even Tim avoiding complaining over oohs and ahhs every time the whale would blow water.

Painting a Hawaiian model

During this session, a long-standing dilemma of mine was resolved once and for all. By now I have no problem in capturing a likeness of a person in a portrait, and that is what I had accepted as the task of the artist. So what if I did not like the way a particular model looked; what if she had a strange looking nose or a double chin? Drawing such things in great detail had made them look beautiful to me while I was drawing them, but let’s face it; a double chin and a big nose is still a double chin and a big nose. The kind of models we typically have in classroom sessions don’t usually come with an inspiring appearance that would lead to a painting for hanging on ones living room wall. And yet, I felt some kind of strange obligation to capture an accurate likeness. It finally dawned on me that an artist has the power and the option, and maybe even an obligation, to do plastic surgery right there on the canvas. Furthermore, while capturing the likeness may be important if a portrait of the person is the goal, it is irrelevant if the goal is to produce a beautiful work of art. Removing the personal details, not only is optional, but also is preferable in many cases. Especially in the case of a painting of an undraped model, including personal details could be considered too private, and adding a classic look to the model is likely to be preferred in art. This defines the difference between a painting of a nude and a painting of a naked person. That it is no sin to make a painting beautiful at the expense of accuracy may be obvious to some, but it was a real, freeing revelation to me.

After six days we moved our hotel and painting sights from Captain Cook north about twenty miles past Kailua Kona village to Keawaiki Beach. This beach, even more beautiful than the last, was associated with a new housing development that had not been stopped by lawsuits. One good result is the requirement that the public beaches be left open and maintained, and this one is spectacular. I sensed that all of the artists were getting better as the week evolved.

Traveling the 15 miles back to the hotel that night took us almost an hour on Highway 19, the only main road around the island. We had just enough time to check into the Hotel King Kamehameha in Kailua Kona, where we would spend our last two nights, before heading to the Kona Café, a local restaurant that had won a reputation for the best Mai Tai’s on the island.

After a mai tai and a bottle of wine with dinner, no one was ready to call it a night, so about half the group moved to the bar and ordered another round. Tim made a toast in his best Irish dialogue.

“Eers to me first love, Iee cudd never ‘ave loov’d er mo’ore. She wuz deef and doomb and awver sexed and owened a lickerr stoor.”

Our last painting day was the first time we had painted in a village. Here I created my last and also my favorite painting of the trip, and I attempted to incorporate most of what I had learned during the week. I liked this study, but like all of the other paintings, I was ready to return and redo it to eliminate a few of the mistakes I had made in the process.

Last painting-Above scene near the Hotel King Kamehameha.

Our last evening began with a visit to Clem’s home in the mountains. Clem, a former student of Tim and now a Hawaiian architect entertained us at his new (still under construction) home, which was strategically positioned by a mountain stream. The walls of Clem’s home were filled with his paintings, and one could clearly see Tim’s influence. Tim could not resist painting the waterfall behind Clem’s home, making for yet another good demonstration. As he finished, Clem walked up with his guitar and began a medley of songs, some of which we all joined in.

Clem singing at the construction site of his new home, with Tom looking on and Rover scratching fleas.

We topped off the evening with a dinner at a nearby German restaurant, the Egelweiss.

The continuity of the past days had given me a learning experience I had never had before, including new knowledge and experience and a chance to transform facts into working knowledge. I finally got that an important job of the artist is to create a work of art, not a copy of a scene. What is out there should inspire but not detract from the work of art being created. It is not a sin for a plein aire painter to adjust a painting, to add or take away from what lies before him to make the painting more esthetically pleasing. The role of art, in today’s photography-dominated world has changed. If detailing what lies in my field of sight were the goal, I could simply photograph it. A good artist designs a work of art that draws the viewer in, leads him around the composition and invites, even entices him to explore colors, shapes, and structure. This is done by strategic placements, emphasis, rhythm, carefully chosen spaces, focus, use of the golden ratio and so on. While no one knows why some of these work, they are known to work. People who look at such a work and enjoy it may or may not know why they enjoy it, but most likely it is because the artist has used good design and composition to make it beautiful.