The WorldWorstTourist Paints France-Another Go with Art Master Tim Clark

Chapter 3-Picnics, Picasso, and Patanque-Collioure

May, 2015

Tuesday-5 May: We made our move to Collioure, with a museum, lunch and painting stop in Ceret. After visiting the Ceret Museum of Modern Art, it was time for lunch. Desperate to paint something and not waste two hours eating, four of us found a small grocery store, purchased bread, cheese, and wine, ate on a park bench, and spent the spare hour painting one of the fascinating alleyways before heading for the bus rendezvous.

Picnic in Ceret

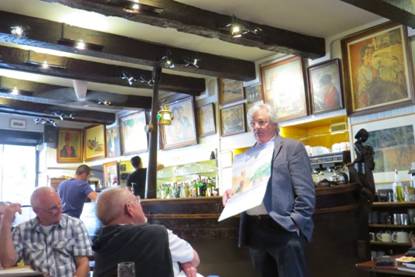

Collioure, another Picasso seaside hangout, an artist’s dream, was our layover for the next four days. The art hotel, Les Templiers, was covered with paintings on every wall and in the bar, which also featured an original Picasso and a large photograph of him standing with the father of the current manager. I could imagine sitting on the same bar stool once used by Picasso

Paintings on hotel walls and a picture of Picasso standing with the hotel proprietor of the day. The white sheet at the bottom of the photograph is an original Picasso drawing of a nude.

Our room balcony overlooking Collioure Bay and the fortress ruin was itself a good painting location and we took good advantage of that. During the remainder of the day we scouted the town for other painting candidates for Wednesday.

Wednesday morning provided a clear sunny day, and within a rock’s throw of the hotel we found a plein air painter’s dream, a small shaded park overlooking the local cathedral reflecting in the marina.

Collioure Cathedral, 11x15, watercolor on paper, painted in Collioure, France

Tim often reviews two mistakes amateurs make in painting towers and structures like this one. First is failure to recognize that shapes at the base of a tower can turn it into an unmistakable and distracting phallic symbol. He related a story of a student’s silo with two round haystacks at the base. Second is inadvertently turning a window pair on a structure into a clown face staring out of the painting, again very distracting. I knew better than add two round bushes at the base of the tower, but inadvertently came dangerously close to a clown face on the red building to the left of the tower. Like writers, artists have difficulty seeing mistakes in their own work. If we could, we wouldn’t need critics. This applies to more that art. The world would be a different place if we could look at ourselves as well as we look at others. “You can see a lot just by looking”-Yogi Berra.

Our painting spot was so perfect that we continued to occupy it for the rest of the day, including a picnic lunch with food from the local marketplace organized by Marriott and a demonstration. Using the same view I had painted earlier, Tim demonstrated scene simplification, shadow connectivity, painting with shapes, vanishing lines and limited palette. Painting shadows first, with just two shapes and two colors, he produced a painting that most people would gladly frame and hang.

Lunch from the local marketplace

A few of us returned to the same place in the evening to try nocturnal painting, something I always attempt at least once on such outings, and Collioure is a great place for it. My attempts at it are usually more fun than productive with mostly unfinished or trashed pieces. Nocturnal painting is essentially a different kind of medium and a different skill, since the eyes don’t see color and contrast in the same way in darkness as in daylight. You have to forget much of what you know about daylight painting. The best I could say about the Collioure nocturnal paint out was that we laughed a lot, had fun, and learned a few things. At the end of the evening, Zeke proclaimed that he now knows the secret. “Nocturnal paintings are actually done in a well lit studio using a photograph.”

Nocturnal View across Collioure Bay including a castle painted the next day

The next day was a productive painting day, and I produced two paintings. In the morning I saw the beautiful castle high above a vineyard that is in the photograph above, best viewed from the east side of town. The early morning sun was behind it, allowing me only a profile. However, anticipating that lighting and shadows would be perfect later in the morning I chose that scene to paint; and so it was. The vineyard in the foreground was an unanticipated pleasant surprise.

Collioure Castle, 11x15, watercolor on paper. Painted at Collioure, France

After a great sidewalk lunch, I moved to higher ground to the fortress that lay between my morning site and our hotel. From the high ground the scenery was perfect; however, it was much too windy to paint in comfort so I continued over the hill towards the hotel. Coming down on the hotel side, I came upon a “patanque” tournament and took a seat among some trees where I had a perfect view of the game from the hill side.

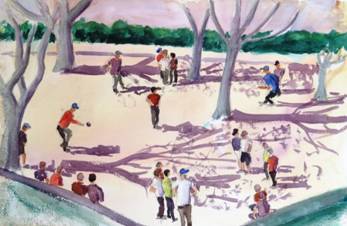

Four or five games were in progress in what appeared similar to English “bowls”. The characters on the field presented an interesting range of posture, which was artistically interesting, and I began to sketch people in the scene. Since bowlers would cycle through the same action over and over, their postures were somewhat repetitive, cycling with the game, allowing me to sketch bits of their frame on each cycle until I had a complete drawing. After successfully creating sketches of a dozen players and onlookers, I set up an easel and produced a painting.

The Petanque Tournament, 15x22, watercolor on paper, painted in Collioure, France

As I get older and more experienced, I find some kinds of new knowledge extremely difficult to learn, especially when older knowledge gets in the way of new knowledge. During this painting trip I learned two important bits of (what should have been obvious) optics knowledge, one of which came from an optics mistake in the Petanque painting; the shadows are painted wider than they really should be. The mistake followed from a series of mistakes, beginning with waiting too long to put shadows in. The sun had disappeared behind clouds, so I had to make up shadows, so I painted what I knew, not what I saw. For the trees I made the shadows as wide as the trees, forgetting that I was looking head on at the trees but at a wide angle to the shadows. This phenomenon of perspective had never occurred to me concerning shadows. [During the critique in the Templiers’ bar that evening, Tim pointed out the mistake and related a funny story, where a student was convinced that her shadows were accurate because she had gone over to the tree and measured them.]

Donald Rumsfeld, speaking about what we know and don’t know, said, “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. ……….. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we don't know we don't know.” Unfortunately, he left out the most problematic of all, the unknown/known”. These are things we believe are known knowns, but are, in fact, untrue. So what we believe is a known known is more like an unknown unknown. My shadow perspective error was the result of an unknown known. I knew that the shadows should be as wide as the tree trunk, but, in fact, was disregarding perspective, so my knowledge was incorrect.

A critique of the day’s work in the Les Templiers bar.

Next -Conclusion-Chapter Four-Uzex, Paris and More Picasso