Chasing an Eclipse in the Faroe Islands-2015

By James Trolinger, the World’s Worst Tourist

March 2015

This is an account of my fourth eclipse chase (others were Australia, China, and Turkey), which hopefully provides also an answer to the often asked question, “Why would anyone travel half way round the world to see something that lasts two minutes?” Part of the answer is obvious; the two-minute eclipse is just a central peak experience that always seems to happen in a place I wanted to see anyway. In addition, it’s an almost annual meeting with a few people with interests similar to mine where I will renew and make new friendships under similar circumstances. Even if the eclipse was covered totally by clouds, the trip would still great, worthy of doing for its own sake. The two minute eclipse is icing on a cake, a peak experience, and I describe the ingredients in detail within this account.

After nine hours airborne we landed in Reykjavik, capital of Iceland, where the majority of Iceland’s 300,000 inhabitants reside. Standing apprehensive and empty handed at a baggage claim conveyer, the instant came when we accepted that we must proceed to a hotel with just a carryon bag, an interesting moment as I reviewed the contents of the lost suitcase and why it wasn’t in carryon. I congratulated myself for bringing essentials on board, especially the heavy down jacket. Even so, the lost bag contained stuff I had spent months acquiring so there was no way I could easily replace everything. That’s when I began praying for the 40 lbs of stuff to show up before our flight to the Faroe Islands to observe the total eclipse of the Sun on March 20, 2015.

The second downer arose as we arrived in Reykjavik at 6:30 AM and realized that we couldn't check into the Icelandic Hotel Marina until almost 8 hours later at 2PM-bad planning. Original plans for a few hours of sleep before exploring were scuttled, so we began exploring Reykjavik on a wet freezing Sunday morning at 2 AM California time. My first day in a new place is unique and intriguing to me, because, at this stage, my only sense of space is a city map, lines on a piece of paper that would soon be translated into my brain as I associate them to the real world. The map didn’t show the icy sidewalks and the freezing winds or the threatening lack of friction under my shoes, sensed with each step. Our first look at Reykjavik with most of the stores closed, dark, cloudy skies, no traffic and few people was not the best first impression of a new place. We walked in a circuit by the Catholic Cathedral, the town center, and a few trinket shops, sizing up the place for a serious walk the next day before returning to the hotel at noon (7AM on our body clocks).

Fortunately, the hotel had a lot of space where we could get comfortable while waiting on our room. Finding two large couches tucked in a side room, we spread out and were soon joined by a couple we had met on a previous eclipse chase. They had been shopping for post cards, proceeded to cover the table with them, and began sorting, addressing, and stamping in assembly line fashion to send to friends and relatives. This is what they do on all of their travels. People do have strange ways to occupy themselves.

After a late lunch, we finally captured a room, found good, free wireless, a large screen TV, no tea making facilities, and a tiny fishbowl bathroom with a frosted glass swinging door open around the edges, unlike any bathroom I have ever seen. Anyone in the room could see and hear pretty much everything going on in the bathroom. Pauline and I were so exhausted we collapsed into bed and slept for 14 hours. Sleep helped me fight off a lingering cold that had started a few days earlier.

I was ready for the elaborate buffet breakfast on Monday, enjoying fresh fruit and all of the things Icelanders eat for breakfast, including smoked salmon, which had me addicted by the end of the trip. After a leisurely breakfast and still no bags, we continued exploring Reykjavik on foot. We began walking in the general direction of the major church partially in a fruitless search for a teapot or water heater but also souvenirs that we couldn’t live without. First stop was Brynja, a local hardware store which could only suggest other possible sources of electrical tea pots. All I managed to acquire that day was a beautiful new Icelandic woolen hat that cost me 60000 Krona, about 50 dollars. Resolution: Never begin a trip without a water heater of some sort. The good news was that every Icelander I met spoke excellent English with little accent. That always gives me reassurance that I can survive in a new place.

The weather was weird with heavy sleet one minute and bright sunshine the next punctuated with gusts of freezing wind that almost swept us off our feet. Umbrellas were less than useless in the sideways rain. We got used to this weather, experiencing it over and over during the next two weeks. As a minimum, our first full day in Iceland was challenging.

The next day, Tuesday, we mounted the bus in a snowstorm at 9 AM to go back to the airport for the one hour flight to Faroe Islands, our home for the next five days. The Faroe Islands, a self-governing realm of Denmark, lies halfway between Iceland and Norway, about 200 miles northwest of Scotland.

View from Hotel Marina as we boarded the bus on the way to the airport headed for Faroe Islands

Faro Islands airport is on Vagar Island, one of 18 Islands. Our hosts split the eclipse group of 110 people into four hotels spread strategically to provide an optimum base that could be established within a few hours of the eclipse. Our group’s hotel was on the next Island, Streymoy, situated on a hillside overlooking Torshavn, the capital and largest city where one third of the population resides. Being on the hilltop gave us a beautiful view of the city, sea, and the next island. To get there we took a 3 kilometer tunnel under the isthmus. Before such tunnels were available, the only way to get between islands was by ferry, and even getting between different parts of individual islands required ferries or dangerous climbs over mountains and bluffs.

View at sunrise across Torshavn and its harbor

I was stunned from the outset by the beauty and colors, which are even more stunning in the summer. The winter color of the grass is yellow ochre complemented by black basalt rocks, mosses, and colorful lichens. The thin, grass-covered soil acts like a soaked blanket covering solid basalt that prevents the water from soaking in beyond the soil. This prevents deep ground water storage forcing the water to run off constantly forming streams of water everywhere. Waterfalls are everywhere streaming down grass covered hillsides. The water supply for the islands is the run off, and daily rains keep it flowing. It is said that February is the driest month simply because there are fewer days for rain. After a few days it occurred to me that this stunning beauty could be a bit deceiving in terms of everyday life in the Faroes due to the problems of a harsh climate in a remote location where the only significant industries are sheep and fish. The guide explained to us that few trees grow on any of the islands for two reasons. The soil is too thin to support deep root system and secondly, the sheep quickly devour any sapling that attempts to establish itself. She explained that without sheep, the Faroe Islands would look totally different.

The ochre colored grass is enhanced by black basalt, mosses, and lichens

A typical view of the sea from almost anywhere on the islands.

A typical view from anywhere in the Faroes with hundreds of waterfalls streaming down treeless hillsides.

Typical waterfall scene

Each day we visited different parts of the islands while our guide explained the culture, history, and geography. Personal interest stories and answers to questions kept a constant dialogue active.

“How do they bury someone in the cemeteries with the soil being so shallow?”

“They bring in lots of dirt, pile it in a spot, then dig in it,” responded the guide.

On one outing we visited Gasadalur on the island of Vagar, a tiny village sitting at the edge of a tall cliff overlooking the sea ringed by tall mountains that cut it off from the rest of the island and, for most of its existence, from the rest of the world. Prior to 2004, the only way in and out of Gásadalur was to hike over the 2000 foot mountain terrain that surrounds the settlement and then trek for more miles to the next village or, alternately up or down the cliff face to a ship brave enough to venture that close to the rocks. The village remained isolated until 2004 when a single lane, 1.7 kilometer tunnel provided an easy access to the rest of the island. Currently18 people live in the village. Once again, the amazing beauty of the place could lead one to forget the difficulties in living there.

Grass roofed buildings in Gasadalur

Grass roofed buildings in Gasadalur

As our bus pulled into a parking place, our guide announced that this would be a lunch stop where we would have 30 minutes for lunch and photos. As she passed out bag lunches, I was amazed to see people in the group desperately opening bags and eating like they hadn’t eaten all week. Realizing that there was a much more interesting way to spend the 30 minutes in such a unique location, Pauline and I stuffed our lunch sacks into our backpacks and began exploring the village.

Finding a perfect spot on a hillside beyond the village I spent my last 10 minutes sketching one of the amazing panoramas before racing back to the bus and finding that most of the group spent their 30 minutes eating a sandwich, lining up for the toilet, and getting back on the bus. Even so, the guide had to round up two people, who, after completing their sandwiches, tried to work in a village tour at the last minute. Pauline and I had our lunch during the bus trip to the next stop.

A beautiful scene from a hillside in Gasadular that I could not resist sketching

Villages in the Faroe Islands typically comprise 5 to 20 houses usually grouped off the main highway close to the sea. In some instances, like the village of Bour, population 70, we left the bus on one end, walked down and through and back to the bus at the other end. After our Bour visit, being behind schedule gave us no more time for photo stops to get back to Torshavn to squeeze in a thirty minute whirlwind tour of the capital. The world’s worst tourist inside me began to squirm.

Village of Bour

After two nights at Torshavn, we moved to Eysturoy our third island to the village of Gjogv. We got to Eysturoy by crossing “the bridge over the sea”, where the isthmus is quite narrow. We had time for several stops along the way, including Saksun, one of the most scenic villages yet. In the tiny village of Saksun, the homes are made of stone, have grass roofs, and are set in a background of spectacular waterfalls providing a scene like something from a story book.

Village of Saksun

We learned that these grass roofs are extremely functional, providing excellent insulation and self maintenance. “Do they hoist a lawmower up there often?”

“ Grass roofs are good for 60 years or more with little or no maintenance, and do not have to be mowed, “ responded our guide.

The Faroe Islands, as well as Iceland, are well endowed with legends and stories connected to the ubiquitous formations. For example, two stones protruding above the waves near Saksun are said to have once been a witch and a giant from Iceland who loved the Faroes so much they colluded to attach a chain and attempt dragging them closer to Iceland. After trying and failing they eventulally turned to stone where they remain today.

The Witch and the Giant, who attempted to move the Faroes closer to Iceland before being turned to stone

Arriving in Gjogv shortly before dark gave me just enough time for a quick walk through the village where I encounterd sheep wandering through the streets but no locals anywhere.

Village of Gjogv

The Faroes are covered with sheep taking advantage of the ample grass supply. They roam, more or less, wild and are rounded up occasionally for slaughter. Surprisingly, their wool is no longer used commercially since it varies so much in texture and color. They don’t even shear the sheep; the wool falls off seasonally. Not surprisingly, lamb and fish are the main sources of meat for the islanders.

Sheep wandering freely in the village of Gjogv.

Eclipse Day

Friday, March 20 was eclipse day with totality predicted for 9:20 AM. So far, all we had seen was snow, sleet, rain, and hail with only brief periods of sunshine. There was never a cloudless day. What person could have ever imagined that bringing people here to see an eclipse was a sane idea? The islands have 50,000 residents and 10,000 tourists were expected for this event. Anticipated problems included traffic jams, parking problems, and trouble in the single-lane roads, especially in the single-lane tunnels.

Single-lane roads are designed with passing spots every kilometer or so where one car moves over and stops while the other passes. Technically they cannot function if there is more than one car between passing places, i.e. bumper to bumper traffic clearly cannot move on a single lane road, and the situation would be disastrous for single lane tunnels.

A weather front was moving in from the west, but there was some hope that it would pass over the sun before 9:20 AM putting us behind it for the eclipse. The place to be was as far west as possible. In previous eclipses it had been practical to move bus loads of people away from clouds at the last minute. This was not such a place so the decision had to be made the day before.

After careful, agonizing analysis, the astronomers selected the air port hotel as the viewing headquarters, since it was the farthest west site that could handle 110 people. Our hosts had managed to take over the entire hotel for the week providing a comfortable place with shelter and toilet facilities. Leaving our hotel at 6 AM for the 90 minute drive to the airport, we arrived in heavy snow and high winds leaving little doubt, at this point, that all we had come 5000 miles to see were clouds. Many people relaxed in the hotel drinking coffee, woofing down cakes, not thinking much about totality. A few diehards had set up telescopes and tripods in the snow with covers keeping equipment dry. A brief trip outside revealed that hope was fading but not entirely gone. Smart people had captured window tables in the restaurant providing limited viewing while sipping coffee.

Just as the moon made its first contact with the sun, something magical transpired. Sudden breaks in the clouds provided a clearer view of the evolving partial coverage of the sun by the moon. Hopes began to rise. Like a last minute scoring in a football game presenting a home team possibility of victory, people rushed to the outside with every manner of filter and camera to point at the sun. Off and on the sun was covered with cloud. At 75 percent coverage the sun became visible through thin clouds, and at 90 percent a big hole appeared in the cloud raising the excitement level to a peak.

For the less initiated, I diverge here to explain the “icing on the cake”, mentioned in the first paragraph. Common expressions circulate among eclipse enthusiasts like “If someone tells you he thinks he has seen a total eclipse but is not sure, you can bet that he has not”; total eclipses are unforgettable. Partial eclipses, by comparison, are irrelevant, and have none of the peak visuals connected with totality. “Seeing a partial eclipse and saying you have seen an eclipse is like standing outside an opera house and saying you experienced the symphony.” Or “Every eclipse lasts 8 seconds.” The transition from partial to totality and back is so extreme, no one can believe it has come and gone; everyone wants it to come back; it seems too short, and all the things you wish you had done but didn’t begin to haunt you because it’s at least a year before your next chance. Beginners will spend much of the time viewing it through a camera hoping to capture the experience in a photograph; that is impossible; you can’t photograph emotions; you can only feel them.

Thirty seconds before totality with over 95 percent of the sun covered, shadows look weird. Eyes are dilating to accomodate the lost intensity, and little contrast exists between shadow and light. Shadows become extremely sharp because the sun is now truly a point source. Many experienced viewers cover one eye to dark adapt before totality begins. The first instant of totality is a special event that happens suddenly as the moon sucks up that last glint, forming the so-called diamond ring. You can observe the moon’s shadow racing towards you when that one last bright spot suddenly disappears and everything becomes instantly dark, like turning off the lights. Now you can look straight at the sun without filters. The surroundings become eerie and unlike anything you have seen with a sunset appearing on all horizons as you stand in the dark amongst highly emotional people. Viewers who have been waiting on and anticipating this moment for over a year sense that suddenly it’s here and it’s not going to last long. Almost always, clouds moving in the wrong direction, threaten to minimize the payoff, adding to the excitement and anticipation, like a gambler waiting for the dice to stop rolling.

Since everything happens so fast, one needs training and rehearsal for an eclipse on how to spend the few minutes; otherwise, totality begins and ends before you even realize you missed a lot of what you had hoped to experience; once totality begins, there is no time to ponder what to do. The night before eclipses, guides give remedial lectures to remind old timers and educate new comers. New comers, not knowing what they don’t know, have no idea of how ill prepared they are. They most likely will not comprehend the instruction until after they have seen the eclipse and made some if not all of the mistakes themselves.

Every novice wants to photograph it, maybe out of habit, because these days tourism and amateur digital photography are practically the same thing. Guides understand the desire but discourage spending much time on photography. Our guide played an audio recording of an eclipse where the voices of several people can be heard. One of the voices is a photographer, who has set up a special camera to record the event. Throughout the recording, the photographer’s calm, business like monologue goes something like, “ Adjusting F stop to insure sufficiently dynamic range. Now zooming to focus on the corona. Bailey’s beads captured.” And so on for the full two minute extent, apparently never viewing it directly with his own eyes, always through the camera. Two others heard on the same recording are simply viewing it, commenting and expressing their feelings. By way of contrast, their comments and reactions are highly emotional, shouting and screaming, partially crying, somewhat out of control, “OH MY GOD! UNBELIEVABLE! SON OF A BITCH!” and so on for the duration. This two minute recording epitomizes the difference between photographing the eclipse and experiencing it. The best advice is to have a camera in hand to take one shot as a “memory shot”, then put the camera away.

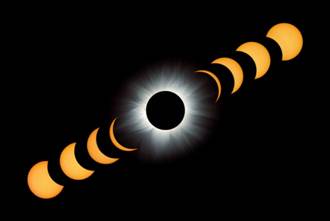

The following photo, extracted from Google Images shows, for reference, how the entire process evolves. Trust me; you will not get photos of this quality.

Professional time evolution photo of the transition through totality over two plus hours with totality lasting a few minutes at the middle. All but the center photo are recorded through a dark filter.

I had promised myself not to waste the valuable two minutes on photography. My plan was to have the camera ready, take one shot shortly after the initial ecstasy of totality, then view it for at least a minute before taking a shot that includes the horizon with the eclipse. Until a few minutes before, I had little hope of even seeing the sun at all this day, so the sudden, exciting comeback was almost overwhelming. A thin cloud layer covers the sun just before totality, not too thick to be a serious problem. I place a filter in front of the camera to sneak in one shot before totality, but the cloud is confusing, since I can almost view without a filter, a dangerous no no. A clear hole suddenly appears in the cloud now providing a completely clear view of a 98 percent coverage. A dark threatening cloud races towards the almost coverd sun. “HURRY, HURRY, I scream at the moon. You can make it, ” just like I would scream for my favorite football star racing towards a winning touchdown as a 200 lb halfback bares down upon him from the side.

It seems like forever the bright point is frozen with the cloud racing towards it. I pull the filter away from the camera, take a shot, then drop the camera to my side, and BAM-totality. A huge relief flows through the crowd and people begin to shout, cry, laugh, and scream with joy. I stare at it in amazement, then quickly observe the horizons, then study the corona. The cloud moves closer and before I think about additional photography, it begins blocking the eclipse. And then everything moves behind the dark cloud. Later we learned that we had just over sixty seconds of viewable totality; It seemed more like two seconds. The realization that the experience ended earlier than expected, brings about that feeling I always get at the end. I yearn for more, but it’s not going to be.

Half an hour before totality-Snow comes and goes-Sun is covered in cloud.

Ten minutes before totality, the clouds open up allowing good viewing of partial eclipse.

A fraction of a second before totality, I take a quick shot and accidentally capture the diamond ring forming.

My “memory shot” of totality, a badly over exposed picture of the corona.

We stand in dark with a bright horizon surrounding us.

A dark cloud begins to block our view of totality.

Individual excitement has peaked and now evolves into sharing experiences with cohorts, each one being a bit different from the other. The ones with successful photos want to show them to everyone in sight, and that exchange continues with the ones with not so good photos being excited with and wanting to share their “memory shot.” At this stage we can’t get enough of seeing and discussing photos of totality, trying somehow to relive or at least reinforce lingering feelings just experienced. Some will regret what they didn’t do during the magical minute and some will remain elated for hours. Most will be glued to watching news accounts and seeing other videos and photos captured at other locations. Some of the locations were not as lucky as we were and saw virtually nothing. The first news accounts described, in error, the disappointment of viewers in the Faroes.

Almost everyone in the group vows to return for the next eclipse sometime next year.

With half a day remaining, we returned to Gjogv, leaving a few hours to explore the village before setting out for a farewell banquet at Torhavn.

Village of Gjogv

Gjogv, meaning gorge, gets its name from the nearby gorge. Walking to the top of the gorge on a very slippery path and reaching an amazing view, I sat for a while on “Mary’s Bench” , so named after Danish Crown Princess Mary, who first sat on it during a visit many years ago. Tourist attractions like this one clearly place the burden of responsibility for safety on the individual. One stupid or even careless move from the top of this gorge would end up with death on the rocks a hundred feet below. There are no signs warning you to keep kids under adult supervision and not much of a fence, but if you like your kids don’t take your eyes off them.

The Gorge at Gjogv

The bus took us to Torshavn early giving two hours either to explore the town or hang out at the banquet restaurant complex, which had a large gift shop and bar. Pauline and I had no discussion in choosing to explore the town, of which we had only a taste on our first visit.

The marina in Torshavn

Fishing is the major industry, and you can bank on the fish being good

Downtown Torshavn

During that visit three days earlier, our 20 minute whirlwind walking tour had raised an appetite to see more. We used the two hours to wander around and soak in the more interesting areas we had seen before, one of which was a neighborhood of grass roofed homes on a hill in the center of town behind the yellow buildings in the figure. During that walk, we encountered one of the tour leaders, who jokingly asked if we were locals, and remarked that he was amazed that most of the people chose to hang out at the restaurant and gift shop.

Grass roofed houses in central Torshavn

The banquets are always nice, featuring the culinary delights of the region and usually entertainment provided by locals. This was no exception, including a wide variety of canapés and a traditional chain dance by some locals. We tasted dishes I had never tasted, such as whale, including some I had not heard of or seen before. The hour’s bus ride back to our last evening in Gjogv was the quietest of the bus rides with most people sleeping for most of the trip.

The ending of the Faroe Islands adventure was the beginning of the optional Extreme Iceland tour, which we had elected to take, having come this far and realizing that we would probably never see this part of the world again.

To be continued---Extreme Iceland, a quest for the Aurora Borealis